Sculpture is a type of fine art made from solid materials and having a three-dimensional shape. Its main objects are humans and representatives of the animal world. Sculpture, like any other type of art, is divided into genres: portrait, everyday, historical, thematic, allegorical, mythical images, etc.

Some experts reject even legalized posthumous castings as unreliable and unethical because the artist could not control or verify the casting work in the new edition. From this point of view, the purity and dignity of an artist's work cannot be preserved after death. Other experts accept bronzes made posthumously under controlled conditions and specific release as valid, even if they are less desirable than lifetime casts. While acknowledging that a one-shot study may be preferable to a generalized statement or condemnation, we believe that both sides share merit.

There are two types of sculpture:

- Round

- Relief

Round sculpture includes works that are viewed from all sides and are not in contact with the plane. You can (and sometimes need to) bypass them in order to appreciate the work from all sides. A relief sculpture is located on a plane. It is usually viewed from the front.

However, the public should be aware of this disagreement. Measures to prohibit international movement in unethical sculptural reproduction. We highly recommend the following. All sculptors must attach a copyright notice to the sculpture that will include their name and the year of the actors. Sculptors must leave clear and complete written instructions or to include in their wills their wishes regarding the future of their works after their death or in the event of their inability to continue working. All heirs and executors of the sculptor's estate must be scrupulous in the performance of their duties and, if necessary, must consult with experts on such matters as those concerning new castings. All posthumous castings or reproductions of the artist's work must be clearly identified by the information provided on the artwork itself, as well as all invoices, notes, catalogs and advertising. This information should include the date of the new casting, the name of the foundry, the size of the edition, and whether the work is above ground or a different scale than the original. All bronze castings from finished bronzes, all unauthorized extensions, all translations into new materials unless specifically condoned by the artist, and all works made while in the public domain must be considered inauthentic. Unauthorized appropriations of works in the public domain should not be taken as accurate representations of an artist's achievement. Accordingly, for moral reasons, such works should: Not be sold by art dealers or auctioneers. Not to be acquired by museums or displayed as works of art. Don't abandon foundries. Clearly identify what they represent by art historians and critics who may write about them. There must be full disclosure of relevant information by those responsible for bronze casting.

Round sculpture was especially popular in Ancient Greece and Rome. In the Middle Ages, interest in it faded somewhat, but it found a “second life” in the Renaissance. One of the first works that brought her back to life was the statue of David (Donatello, 1408-1409).

According to its purpose it is divided into:

- Monumental

- Monumental and decorative

- Easel

- Small sculpture

Let's look at each type using examples of works presented in St. Petersburg.

Each actor should have information about the date, foundry, edition size, and whether it is an increase, revaluation, or change to the final medium used by the artist in his or her life. Additional Information, listed above, should be part of the documentation that accompanies the sculpture. Subject to the above, quality of life made by or under the artist's supervision and with his or her approval as a result of publication is desirable.

To be considered less desirable are posthumous castings authorized by the sculptor, which will be cast from his or her plaster, wax or terracotta sculptures under controlled conditions and good quality compared to what the artist achieved.

Monumental sculpture

Monumental sculptures are usually dedicated to significant historical events or have cult memorial significance. They are characterized by large scales and harmony with the architectural and spatial surroundings. This includes monuments and memorial ensembles.

Monumental sculptures are usually dedicated to significant historical events or have cult memorial significance. They are characterized by large scales and harmony with the architectural and spatial surroundings. This includes monuments and memorial ensembles.

Posthumous castings of finished bronzes, unauthorized casts such as those made as a result of work in the public domain, extensions not supported by verifiable instructions from the artist, posthumous transfer of carvings to bronze, or work in any medium other than wax, terra cota, and plaster that is bronze cast for the first time, undesirable.

The initial draft of this statement was prepared by Albert Elsen, president of the College Arts Association. Taylor, Director of the National Collection fine arts, representing the Association of Art Museum Directors; Max Wasserman, Fogg Art Museum; Edward Wilson, sculptor, Artists' Committee, College of Art Association; Virginia Zabriskie, Zabriskie Gallery, representing the Art Dealers Association. The ad hoc committee included Antonia Boström, J. Paul Getty Museum; Alan Darr, Detroit Institute of Arts; Bob Emser, independent artist; John Steele, Detroit Institute of Arts; and Elon Van Gent, University of Michigan.

Probably one of the most famous works of art in St. Petersburg, which belongs to monumental sculpture, is the “Bronze Horseman” - a monument to Peter I. This is the work of the French sculptor Etienne Maurice Falconet, completed in 1768-1770. Peter's head was sculpted by his student, the French portrait painter Marie-Anne Collot. The snake was sculpted by the Russian sculptor Fyodor Gordeevich Gordeev. In 1778, Falcone had to leave Russia, and the work to complete the monument was entrusted to the famous architect Yuri Matveevich Felten. The monument was opened on August 7, 1782.

Roman sculpture is characterized by an eclectic character and an overlay of empire that has signified the world for centuries. The art is a mixture of excellence and classicism, with aspirations of realism and oriental styles summed up in stone and bronze sculptures of unsurpassed beauty.

As in painting, the Romans also suffered from Greek influence in sculpture, but developed a style of their own as they came to dominate the world. Roman sculptors worked on stone, precious metals, glass, terracotta, but their striking feature was even on bronze and marble. The latter dominates most works of art.

First of all, Falconet wanted to show Peter I not as a victorious commander, but as strong personality. The Emperor is depicted in an emphatically dynamic state. The pedestal in the form of a huge rock is a symbol of the difficulties Peter I overcame, and the snake introduced into the composition is the “hostile forces” that he easily defeats.

Monumental and decorative sculpture

Under Greek and Hellenistic influence, Roman sculpture was made into copies, and the result depended on the skill of the sculptor. There was a school of crafts in Athens and Rome. Directors included Piteles, Archesolos, Evander, Glykon and Apollonios. It was the custom of the Romans to produce miniature copies of Greek originals, often in bronze. The Greek sculpture of Orestes and Electra was reproduced in miniature.

The massive bronze sculptures display statues of emperors, gods and heroes. Researchers often say that there are two different markets for Roman sculpture. The first is aristocratic, oriented towards the ruling class, with more classical and idealistic sculptures. The second is provincial, aimed at the middle class, more naturalistic and with a type classified as emotional.

Monumental and decorative sculpture is used in the design of facades and interiors of buildings, bridges, triumphal arches, fountains, small architectural forms, creates the integrity of the perception of the garden and park ensemble. The sculpture can serve as a support in an architectural structure (Atlantes, caryatids) or decorate buildings (pediments, portals, stucco lampshades, panels).

Monumental and decorative sculpture is used in the design of facades and interiors of buildings, bridges, triumphal arches, fountains, small architectural forms, creates the integrity of the perception of the garden and park ensemble. The sculpture can serve as a support in an architectural structure (Atlantes, caryatids) or decorate buildings (pediments, portals, stucco lampshades, panels).

Like the Greeks, the Romans also liked to represent their gods in statues. And this custom did not change when emperors began to compare themselves to gods and literally revived divinity. Emperors are depicted in statues as imposing and authoritative. Less impressive, but no less beautiful, were the statues of spirits that protected houses. Long-haired figures in tunics and sandals are carved from bronze.

The emperors were cut out as an overlay of numbers. The portrait, the human bust, is one of the factors that distinguishes Roman sculpture from other arts. Realism - main feature sculptors, with details of scars, aging skin, flabby and showing the reliefs of time, like wrinkles. It is often said that Roman sculpture tells the truth.

One of the brightest examples of monumental and decorative sculpture are the figures and reliefs on the Admiralty building in St. Petersburg (1806-1823, architect A.D. Zakharov). The reliefs in the pediments of the side porticos depict greek goddess Justice Themis, rewarding warriors and artisans. The Central Arch has a flank of statues of nymphs standing on high pedestals, carrying globes. At the corners of the first tier we see figures of ancient heroes: Alexander the Great, Achilles, Ajax and Pyrrhus. Above the colonnade there are 28 sculptural symbols: fire, water, earth, air, four seasons, four cardinal points, etc.

Another feature of Roman grandeur and realism is found in architecture. All the buildings celebrated victory in military campaigns and domination of the world. This refers to the Arch of Constantine, built in Rome in the 315th century AD. Constantine's army showed superiority in the war.

This distinctive sign Roman art in relation to Greek; while the former was characterized by realism, he used mythology to depict his victories. Roman sculpture became famous for its great statues of emperors, gods and heroes.

Easel sculpture includes different kinds sculptural composition - head, bust, figure, group; various genres - portrait, plot, symbolic, allegorical or animalistic. Works of easel sculpture are designed to be viewed at close range. That is why it is believed that these works “conduct a dialogue” with the viewer. They are sometimes even more intimate. Each individual person can see, for example, in a bust something of his own, something that he will understand.

Easel sculpture includes different kinds sculptural composition - head, bust, figure, group; various genres - portrait, plot, symbolic, allegorical or animalistic. Works of easel sculpture are designed to be viewed at close range. That is why it is believed that these works “conduct a dialogue” with the viewer. They are sometimes even more intimate. Each individual person can see, for example, in a bust something of his own, something that he will understand.

There are countless examples of this type of sculpture in St. Petersburg. Walking around the Hermitage and looking at either the bust of the Apostle Paul (A. Algardi, 1640s) or the Portrait of Voltaire in a toga (J.A. Houdon, 1778), Portrait of Emperor Peter I (B.K. Rastrelli, 1723 -1729) or the statue of Shooting Cupid (F.J. Bosio, 1808), you invariably touch works of easel sculpture.

Architectural decoration took various forms in the 6th century BC. e., giving the buildings an elegant appearance. In addition to large, hollow inside statues, sometimes as tall as a man, as well as one-sided antefixes, Etruscan temples were decorated with relief slabs with plot images and ornamental patterns. The paint preserved on terracotta products makes it possible to talk about the peculiarities of their polychrome. Temple sculpture among the Etruscans was predominantly terracotta rather than stone or bronze - heavy on adobe walls and wooden supports. It served as decoration when the surfaces of the beams were covered with patterned terracotta friezes, and fulfilled the tasks of the cult with statues of deities and mythological figures and plot scenes on antefixes and reliefs.

The most interesting examples of Etruscan temple sculpture come from the heyday of architecture, the end of the 6th - beginning of the 5th century BC. e. The principles of decoration of buildings can be judged from their clay models. The surviving terracotta likeness of a pseudoperipterus from Vulci shows two figures reclining on the pediment, large acroteria on the sides and a number of small antefixes on the long sides of the temple.

The patterns on the antefixes, the figured endings of the callipters that covered the seams between the lower tiles - salts, were repeated along the entire long side of the temple. The development of plastic forms of Etruscan antefixes goes from generalized to more detailed and expressive at the end of the 6th century BC. e. The sculptors loved to decorate antefixes with the faces of the gorgon Medusa with a wide gaping mouth, protruding tongue, and rings of snakes around her head. The bulging eyes and raised eyebrows of the demonic creature convey its rage in expressive forms (ill. 84, 85).

Such artistic completions of ordinary tiles carried, in essence, several semantic loads. Firstly, the antefixes depicting demons were a kind of apotropaic amulets that protected the deity’s house from evil forces. The medieval chimeras, which later adorned the ceilings of European cathedrals in abundance, go back to them as distant prototypes. At the same time, the decorative significance of antefixes is great: the writhing hair of a gorgon or other similar details were perceived next to the calm surfaces of the walls as a pattern that enlivened the appearance of the temple. Traces of paint were also preserved on the surface of the antefixes: the pupils, hair, eyebrows, lips of the gorgon and other characters were tinted, which increased the elegance of the building. And finally, antefixes, with the terrible faces of a gorgon, often served as drains: through the gaping mouth of the monster, the rainwater. In such Etruscan monuments there was a close unity of their functional, plot-semantic and decorative essence, characteristic of many ancient works.

Etruscan sculptors were very resourceful and witty in choosing characters for antefixes. Their attention was attracted not only by the ferocious faces of the gorgons or the funny, ugliness faces of the Sileni, but also by the beautiful heads of young maenads. Such antefixes of the 6th century BC. e. are kept in the collection of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow and in the Kiev Museum of Western and Eastern Art (ill. 86, 87). The strictly frontal image of the faces of the maenads, the large round earrings decorating the ears slightly turned towards the viewer, large, wide-open eyes and raised eyebrows in surprise are interpreted in the spirit of sublimely calm, universal archaic art.

Antefixes of temples of the late 6th - early 5th centuries BC. e. extremely varied in shape. Obviously, this was the most intensive period of architectural decoration in Etruscan history. The Odessa antefix with the face of a gorgon facing the viewer is flat, and the ears, hair, mouth, and eyes of the demon are indicated in low relief, in which the graphic element predominates. In contrast, the Kiev antefix in the form of a woman’s head with a diadem and large ear pendants is plastic. The facial shapes that complete the callipter seem to continue the direction of the tiles and are extended forward. The sculptor enlarges the facial features - the eyes with green pupils, a huge forehead and a sharply protruding nose seem huge. Paint plays a big role here, reviving the archaically weighty plastic forms. There is something special in this anthropomorphic appearance that makes one guess in it a mythological, humanoid creature.

The Moscow antefix is more elegant. Plastic, graphic and pictorial advantages are harmoniously combined in it, although the quality of its execution is low. The diamond-shaped multi-colored patterns of the pedestal, colorful clothes and hairstyle of the woman made very beautiful roof building bearing these graceful decorative reliefs.

The artists' use of depictions of sea demons - the Gorgons and Typhon - is associated with the great importance of the sea for the Etruscans, who were known not only as excellent sailors, but also as cruel pirates. Antefix in the form of Typhon belongs to the best examples decorative decoration of the temple (ill. 88). The monster's legs are likened to long snake bodies, intricately wriggling and ending in heads. The coarseness of Typhon's base features, which reproduced the face of some port slave-loader, was clearly exaggerated by the sculptor 18 . Typhon - a terrible winged snake-footed creature - acts here as an apotropaic amulet. At the same time, the silhouette lines of his figure are designed to enhance the elegance of the roof with their decorative character. Etruscan sculptors, always resourceful in combining the practical and artistic, used certain details, in particular objects in the hands of Typhon, to increase the strength of a high-placed and exposed strong winds antefix. The long beards of fantastic snakes also served to strengthen their heads.

18 (The Etruscan master never showed such rude faces when depicting gods.)

The compositions in the antefixes depended on how they looked from below. When approaching the temple, the frontal images of Typhon or Gorgon could be seen from afar. When urban development did not allow this and it was necessary to walk along the building, reliefs with lateral movement, similar to a maenad leading a drunken silenus, were placed on the antefixes (ill. 89). The Etruscans, like the ancient Greeks, tried to correlate actions on the frieze, antefiscus or metopes with movement real people near structure 19. This demonstrated the unity of artistic images with reality, one of the elements of ancient realism. At the same time, no matter how emotional the images of statues and antefixes of the 6th - early 5th centuries may seem. BC e., movement always seemed to be limited by invisible boundaries, without breaking out of them.

19 (In this regard, it is necessary to recall the composition on the northern frieze of the treasury of the Siphnosians in Delphi, which took into account the movement of pilgrims along the sacred road, not only passively contemplating the victory of the gods over the giants, but as if taking part in the battle with them and thereby, after physically washing in Kastalskoe key, purified spiritually before entering the temple of Apollo (see: Sokolov G.I. Delphi. M., 1972, p. 75).)

Etruscan temples of the second half of the 6th century BC. e. decorated not only with antefixes, but also with terracotta, 20-30 cm high friezes with various compositions. The slabs of the temple in Veletri depict gods seated on folding stools (13, ill. 37 a); one of the celestials turned sharply back, as if in a conversation with Hermes, who was listening attentively to him. Next to them, two standing characters seem small. The somewhat monotonous archaic system uses a rhythmic repetition of torsos, legs, and stools. The upper parts of the figures are shown more freely in hand movements, poses, turns of heads, bowed shoulders, and various hairstyles. The archaic order here is enlivened by the complication of the compositional rhythm.

On the frieze from the temple of Poggio Buco in the procession of fallow deer, deer, lions, as well as fantastic monsters - sphinxes, griffins - something new is noticeable - detailed, skillful modeling of animal bodies, a more perfect image of bold turns and movements (ill. 90). One can also feel here a peculiar stylization of Orientalistic techniques, known from monuments of the 7th century BC. e. The master captured a chariot with a charioteer driving a pair of fast running horses (13, ill. 39 a). Like other similar friezes, which often had an ornamental frame, the frieze from Poggio Buco was bordered at the top by monotonously repeating teeth of the cornice, and at the bottom by two interlacing ribbons. Recent excavations at the acropolis of the Etruscan city of Aquarossa have revealed terracotta relief friezes that decorated the buildings. One of them depicts two warriors with shields and spears, Hercules fighting a Cretan bull, charioteers mounting a chariot harnessed to winged horses, the other shows a banquet scene. The blue and brown tones in which the figures are painted are also repeated in the alternation of monotonous plastic protrusions above the frieze (17, p. 64).

Slabs similar to the square Greek metopes were not found in Etruscan decorative sculpture. Although the Tuscan order is close in its stylistic qualities to the Doric, Doric elements are alien to Etruscan architects, who gravitated more toward the Ionic system of decoration.

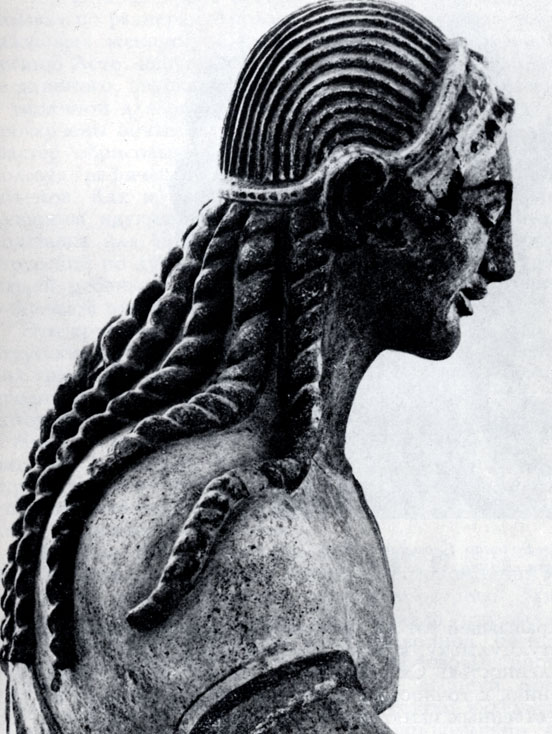

Decor of Etruscan temples of the late 6th century BC. e. included and round sculpture- sometimes large terracotta statues. The best preserved examples are from the sanctuary of Minerva in Veii, executed, it is believed, by the master Bulka, who depicted the dispute between Apollo and Hercules over the Cyrene hind. The statue of Apollo suffered less than others from time and damage. Compared to the sublimely calm images of the ancient Greek archaic, the Etruscan sculptor’s god of light amazes with his dynamism and expression (ill. 91). The wide step, leaning forward body and resolutely directed gaze ahead are filled with great emotional power, expressed by the movement of the huge figure and tense facial features. A massive decorative stand in the form of a palmette and two writhing volutes at the feet ensured the strength of the heavy statue, which exceeded the height of a person, hollow inside, but with thick walls.

The wide folds of Apollo's clothing fall almost parallel. His hairstyle is also shown with monotonously bending strands. Only hair lying loosely on the shoulders and going down the back, braided in pigtails, softens the harshness of these repetitions. The surface of the exposed clay is covered with a layer of preserved red paint. The almond-shaped outlines of the eyes and the archaic smile are reminiscent of Greco-Asia Minor works. However, the sharpness of facial features and the confidence of the gaze, characteristic of the Etruscans, are not characteristic of Hellenic images (ill. 92).

Etruscan sculptors always sought to express the essence of a particular deity. More sharply than the Greek ones, they focused attention on the majestic and wise calmness of Jupiter, the courageous restraint of Minerva, and the trickery of Hermes (ill. 93). On the face of Hermes, whose head was preserved from a statue that adorned the same temple in Veii, the master showed a sly smile, revealing the meaning of the god with great certainty. The Etruscans' penchant for concrete thinking, for accuracy and clarity in the reproduction of character traits in artistic monuments, was felt already at the end of the 6th century BC. e. These qualities perceived by Roman sculptors would later be brilliantly embodied in their numerous sculptural portraits.

![]()

Under the altar of the temple in Veii, another statue was found, similar in size to Apollo and Hermes, depicting a woman with a child on her shoulder, possibly the goddess Leto, carrying little Apollo. The folds of her long chiton, descending to her heels, are marked with the care typical of Etruscan masters and are drawn at almost equal distances from each other. The master outlined the shapes of the body, back, and legs with them, using graphic means in the interpretation of plastic volumes. As in the statue of Apollo, a massive stand is placed between the shins of the woman walking with long strides to strengthen the sculpture. The image is purely Etruscan in spirit: the movement of the figure, the gesture of the hand holding the child - everything in its plasticity testifies to great emotional tension.

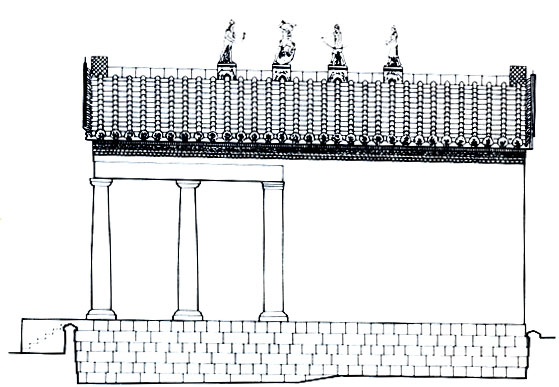

These large terracotta statues were located on Etruscan temples, obviously not in the same way as in the ancient Greek triangles of the pediment, but on the ridge - the upper longitudinal beam gable roof(ill. 94). On some urns, in particular from Cerveteri (17, ill. B), as well as on archaic buildings in Acquarossa, the ridge beams were actually decorated with various figured clay attachments. A terracotta head was also fixed on the vaulted lid of the funeral urn mentioned above.

Widespread in the 6th century BC. e. received small bronze sculptures in connection with the development of rich metal deposits on the Etruscan island of Elba. Cult and dedicatory figurines of warriors, gods and geniuses, household items - chariots, bronze cists, lamps, mirrors, as well as weapons and armor were cast from metal. Bronze figurines ranging in size from 15 to 40 cm were overwhelmingly offerings to the deity. Terracotta figurines, similar to those widespread in Greece, in the 6th century BC. e. there was little in Etruria.

Bronze items from the 6th century BC. e. indicate innovations and successes in the development of this type of plastic surgery. The range of subjects expanded significantly: male and female images, figurines of animals and people, naked and clothed characters were created. The attention of the masters was attracted by gods, warriors, musicians, and runners. The figures were depicted bolder and freer, although calm compositions still predominated. The plasticity of the body became more expressive, the movement was more natural, the plastic interpretation was more perfect, greater harmony and conformity were felt in the gestures of the hands and the restrained movements of the torso.

In the bronze figurine of a warrior from Brolio in the collection of the Florence Archaeological Museum, the sculptor adhered to the manner of the static position of the figure, characteristic of the early periods of Etruscan art. Monuments from the end of the century are more dynamic. Hercules from Fiesole, with the skin of a lion thrown over his head and descending to his knees, moved his left leg forward and raised right hand; the body and chest are still interpreted in an archaic generalized manner (24, ill. 24 c).

Minerva is shown calm and majestic in a figurine found near Florence. The pointed helmet on the head, the peplos falling to the toes, the frontal position of the torso, the straight gaze - everything here is dictated by the sculptor’s desire to create the image of a decisive and steadfast goddess (24, ill. 24a). An energetic and wide-stepping warrior with free movement of his arms, perhaps the god Mars. He has a high helmet on his head, his body is hidden under a shell, and he has greaves on his legs (ill. 95). The interpretation of the body, arms, and legs in such seemingly skinny figures is very conventional. There is still a long way to go before modeling the surface, the body is elongated, the head is small.

The Etruscan love for decorating objects, noticeable in bucchero-type vessels, was also manifested in the decoration of various bronze objects: chariots, tripods, candelabra, mirrors, urns.

Bronze figurines were often animated large boilers- lebes, situlas - vessels with movable flip-over handles, cysts. Along the edges of a large lebes from San Valentino, near Perugia, the master placed reclining lions and sphinxes, well matching their shapes with the spherical surface of the vessel; sharp heads turned These guards, protecting the contents of the cauldron from evil forces, have the wriggling wings of a sphinx and the tails of predators. The shapes of the lebes and the tripod on which it rests are designed in the same style. The silhouettes of the three-part tripod panels with relief images are flexible, the movements on their friezes are leisurely, the stand for the lebes is likened to the petals of a blossoming flower, everything is decided in calm harmonious lines. In the scene of Peleus’ pursuit of Thetis, placed on a tripod, where a snake and a lion are shown as a sign of the goddess’s miraculous transformations, the figures have smooth outlines (23, pp. 27-28). Emphatically generalized, only in one place enlivened by sharp folds of clothing, they merge with the background surface.

Etruscan tripods in the 6th century BC. e. were decorated with complex bronze patterns, almost lace-like in their elegance, as if flowing from the upper stand along the connections of the three legs. They often combined ornamental and plot compositions. Plant motifs formed intricate interweavings with animal figures, often showing fierce fights; you can see how animals squabble in rage, heroes overcome terrible monsters, the world in such compositions seems to be an arena of incessant bloody struggle 20 .

20 (Such scenes evoke images from Scythian works of animal style, as well as some compositions of the pediments of archaic temples in Greece.)

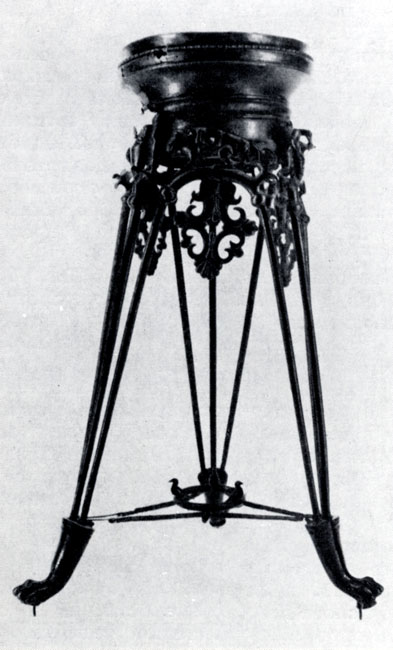

Bronze tripod from the Hermitage collection, 6th century BC. e. from Vulci - a monument, the likes of which were created quite a lot in this city for the cult needs of temples and sanctuaries (ill. 96). This is an example of how Etruscan artists decorated an object necessary in everyday life, making it a work of art. Legs in the form of bushings, ending with sculptures of animal paws, support the entire structure. Bronze rods, coming out three from each sleeve, rise up. The middle of these three rods have their upper ends, and the side ones, connected to the side of the adjacent bushings in the form of an arch, serve as a support for the bowl. The tripod is richly decorated with reliefs, as if the master tried to hide behind the active figures of people and animals a design that is beautiful in its ingenious simplicity. The basis and decor, substance and image here turned out to be organically fused and each fulfilling its role. The upper parts of the leg bushings are held together by rods decorated with a ring with birds sitting peacefully on it. The arches of the rods connected at the top seem to sprout with buds and leaves of fantastic plants, like later the details of Gothic cathedrals. They descend from these arches openwork patterns, similar to bronze lace, repeating the motifs of palmettes, volutes and other ornaments. On two arches there are predators tormenting victims - a lion gnawing a doe, and a lion attacking a bull. On the third arch, a man defeats an animal. Grabbing the horn, Hercules forcefully bends the mighty Cretan bull, which begins to yield to him. Hercules also performs other feats here: he fights the Nemean lion, carries a Calydonian boar on his shoulders, and above the third rod Eurystheus is shown, hiding in horror in the pithos at the sight of the monster. Birds, animals, plants, people are perceived here as a wonderful decor, enlivening not only the object - the tripod, but also the harmonious structure of the base, the plot expression of which it is.

In the bronze ornamentation of the tripod, Egyptian motifs are combined with Greek forms and elements of oriental patterns. The imagination of the Etruscan masters of that time is inexhaustible in the richness of all kinds of images; real motifs are intertwined with fabulous and legendary ones. The lines and forms are not inferior to the Scythian animal style in terms of internal energy. Something similar will later be found in the art of the barbarian tribes of Europe. All these bronze openwork decorations are designed primarily for contemplation on one side and are similar to reliefs without a background, in the compositions of which artistic value have contours of voids between the figures.

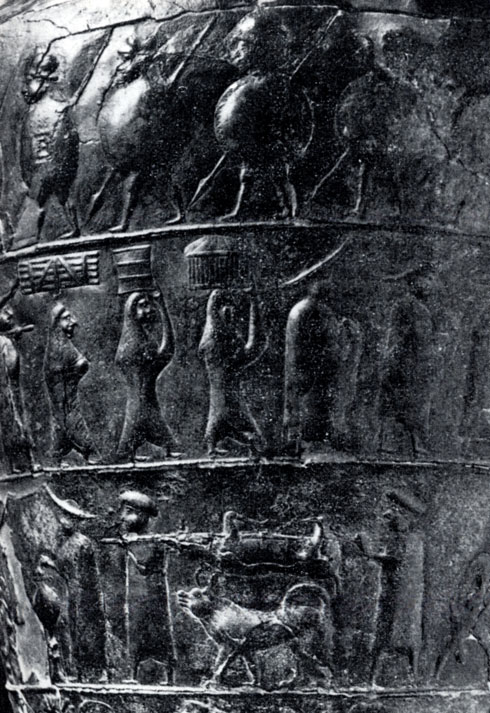

Bronze items from the 6th century BC. e. decorated not only with reliefs, but also with scratched or engraved drawings. Figured friezes were placed on the wide surfaces of the situls. On the top frieze of a situla from Bologna, used as a funeral urn, warriors with swords and spears march one after another (ill. 97), the second is filled with a solemn procession, the third is dedicated to scenes from rural life, and the fourth, lower one depicts real and fantastic animals ( 6, ill. 25). Another situla of the Bologna Museum (Fig. 98) has three ornamental and three figural friezes. On the bottom - animals and birds, on the middle - warriors with shields and spears, on the top - chariot racing. In such compositions, the rhythmic repetition of patterns or identical figures is strictly observed. Sometimes craftsmen use different directions of movement in adjacent friezes and thereby achieve an overall harmonious balance.

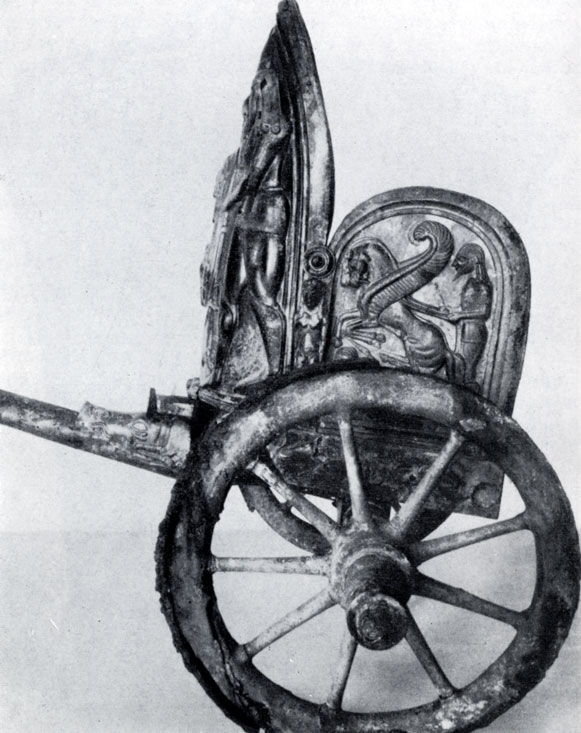

Chariots of the 6th century BC were also decorated with bronze reliefs. e. The middle and two side plates of the cart from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York are completely filled with figurative images (Fig. 99). On the front wall two figures are reproduced holding a helmet and a shield. On the low side blades of the chariot a warrior is shown on winged horses.